Lounging through Lucknow Lore | By Nidhi Mishra (Founder of Bookosmia)

Nidhi Mishra takes us on a nostalgic journey through the syncretic elements of Lucknawi culture

“I know you are from Lucknow, but must our daughter lose marks in your mother tongue for some whimsical assertion of your Lucknawi roots?!” my (Kannadiga) husband asked incredulously. He was even more stunned to see the hesitation I had in giving the obvious answer categorically.

I had barred my daughter to use the (correct) word ‘main’ in Hindi, a perfect translation of ‘I’ in English and all its variations (mera, mujhe etc) and instead had raised my girl to refer to herself as ‘hum’ (literally translates to ‘we’ in English). Her Hindi teacher had rightfully pointed out that it was not the right usage. In my mind I agree, but in my Lucknawi heart I think, “Why not?”

My brother recently pointed out that it is not to do with the interweaving of Urdu, since Urdu ghazals liberally use the word ‘main’ and its variations. Like so many other things about the city, this is another ‘unreasonable’ characteristic of belonging to Lucknow.

It will be exactly two decades since I left Lucknow now, but the immense assimilation of cultures, language and location has not dulled the city’s flame in me. I recall these beautiful lines by the two-times Man Booker prize winner, Hilary Mantel: “We can’t excuse the past, just for being over and done. We can’t say, ‘all water under the bridge’…The past is always trickling under the soil, a slow leak you can’t trace.”

I find it hard to define Lucknow, as must be the case for any city, for that matter. Yes, you can always sum it up in its Ganga Jamuna tehzeeb and lehza (syncretic culture), but sometimes it is hard to keep things brief. I depend heavily on people, incidents and anecdotes to illustrate the spirit of the city, as I had known it.

In Lucknow, boundaries were blurred.

I did all my schooling in Lucknow, at the famous now 148-year-old old Loreto Convent, fluent in every Christian hymn and lover of every Christmas carol. My brother, who went to St Francis, grew up in a similar ethos. My best friend in Junior School was Saba and my brother’s was Danish. We lived a stone’s throw away from the iconic Hazratganj area. But we were never raised to notice religion in our surroundings or friends. How I wish I could make my kids unaware of these distinctions as well.

My grandfather was a very respected person. Legend has it that the level of his anger could be measured by how deep his transition was from conversational Hindi to Urdu. So, when he opened the conversation with “Barkhurdaar, aap nihayti ahmek insaan hain (Sir, you are a scoundrel; spoken in Urdu),” it was a red alert for anyone planning an escape from a beautiful sounding reprimand.

When my father talks of poetry, there is a special flicker in his eyes. He is a prolific writer himself and listening to Begum Akhtar with him on his long-playing record player, has been one of the finest pleasures of my life. It is no wonder that my mother is a naturalised Lucknawi who joyfully watches Urdu poetry gatherings, mushairas, on You-tube. My father still displays extraordinary pride when he shares that the bungalow in which Begum Akhtar resided, was leased out by our family. I think he relishes the fact that in some distant, dreamy way, there is a piece of paper which houses both his and the Begum’s name.

In Lucknow, everyone had a poetic tongue.

“Muskuraiye, ki aap Lucknow mein hain (Smile, now that you are in Lucknow),” greets the billboard as you enter the city.

What happens when you end up brushing past another vehicle on the road? Freezing glares, verbal assault, even a fist fight? In the Lucknow of my time, you would hear the other person say, “Gareeb aadmi hain sahib, gaadi chadha deejiyega? (I am but a poor man sir, run me over?)” You would have no option but to hand over your melted heart to that person and drive away.

Cycle rickshaws were ubiquitous in my time. The rickshaw pullers, who would physically pull our weight (though with the help of wheels on the vehicle) and had to put in so much manual labour, would always cheerfully ask, “Bataiye janaab, aaj kahan le jaaenge? (Please tell Sir, where will you be taking me today?)”

The Nawaabs of Lucknow

We grew up with not just love for the good life, but also respect for it. ‘Shaukeen’ (aficionado) is a word which I find hard to translate but synonymous with Lucknow life.

My Dadi (grandmother) was the highlight of my growing up years and in my mind carried the charms of the city in her personality. Unlike most women from her time, she was extremely well-educated for her time (and even for today) with a master’s degree in literature and having joined my grandfather when he went for higher studies to England. It was not rare to hear her casually weave some Latin phrase, like Nil nisi bonum* into a conversation. She was responsible for my (rather early) transition from Nancy Drew and the likes to Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca, opening up the gates of romantic literature.

Many years later, on my grandfather’s Shraadh (annual death ceremony), while conforming to the traditional brahmin rituals and serving of traditional food for the supposed appeasement of my grandfather’s soul, Dadi would also make sure that the holy cow was also served his favourite burger. She brushed aside stereotypes with little pomp, much panache and a lot of understated elegance. And in all of this, she personified the spirit of Lucknow to me.

Another differentiating trait was about taking life easy. While my kids are often told, “Early to bed, early to rise…,” I remember hearing the saying, ‘Aaram badi cheez hai, munh dhak ke soiye, kis kis ko yaad keejiye, kis kis ko roiye (Comfort is a big thing, relax and sleep peacefully. is there any sense in remembering and crying over people)’. I would love to trade a little bit of my ‘fast forward’ with a little bit of that pause.

This love for ‘the good things of life’ was not restricted to a certain class or community.

I remember hearing that the vegetable vendors would sell their goods with very unique descriptors- ‘Laila ki ungliyan, Majnu ki pasliyan (Laila’s fingers, Majnu’s cartilage)’ uniquely referred to ladies’ fingers and gourds. There was a love for culture that transcended classes and income levels. Another vegetable vendor was famous for his claim ‘Begum (Akhtar) ke bag ki sabziyan(vegetables from Begum Akhtar’s garden)’. No wonder literature and music were literally fed to us!

Culture was not something which was curated by and for the elite. It was on the road, it was in the offices– it was everywhere.

Well before I read about Keynesian theory in B-school, the tourist guides at the marvelous Bhool Bhulaiya (meaning labyrinth) had regaled some wonderful lessons around unemployment, wages and labour. It is said that around 1780, the region was badly affected by famine. The fourth Nawab of the Awadh Province, Nawab Asaf-Ud-Daula Nawab thought of building this structure as a way to generate employment as well as provide food to people in return for their services. The people were too proud to receive compensation from the Nawab without earning it (equating it to alms). Hence a part of the monument would be constructed during the day by part of the labour, while the other part brought it down at night. This ensured that the Nawabi pride of the common man was intact, by earning his living. It took fourteen years for the monument to be completed.

Things change, places do too

I hear that now the rickshaw pullers of Lucknow (like in any other city), come straight to the point, “Itna paisa lagega. (It will cost you so much).” Not that there can be anything wrong with that statement — to the point, upfront and efficient. But poetry never cared about efficiency, nor did the Lucknawis of yore.

Migration, politics and so much more has changed the fabric of the city a lot. William Dalrymple devotes a full chapter to what ‘Lucknawi’ used to mean, in his book Age of Kali. Notice the past tense in this whole piece. Sometimes I wonder if we are just romanticizing the idea of Lucknow. Did it really exist or was it just a dream!

Khwab tha shayad!

Maybe it was a dream

Khwab hi hoga!

It must have been a dream

Sarhad par kal raat, suna hai, chali thi goli

Have heard that last night across the border, some shots were fired

Sarhad par kal raat, suna hai

Have heard that last night across the border

Kuchh khwaabon ka khoon hua hai

Some dreams have been murdered.

-Gulzaar Sa’ab

Disclaimer: I know no conversation on Lucknow is over without a special mention to its culinary delights. Unfortunately, as a vegetarian I disappoint there, with little meat to offer. Though I can swear, you would not get better kebabs in the world. Apologies for all the Hindustani in the piece for the English only readers. I found it difficult to talk of Lucknow without a splash of Hindi- Urdu.

* Latin for indicating that it is socially inappropriate to speak ill of the dead as they are unable to justify themselves.

===========================================================

This article was first published in the Borderless Journal and republished in countercurrents. org. I shall be forever grateful to these fantastic platforms for including my voice.

=========================================================

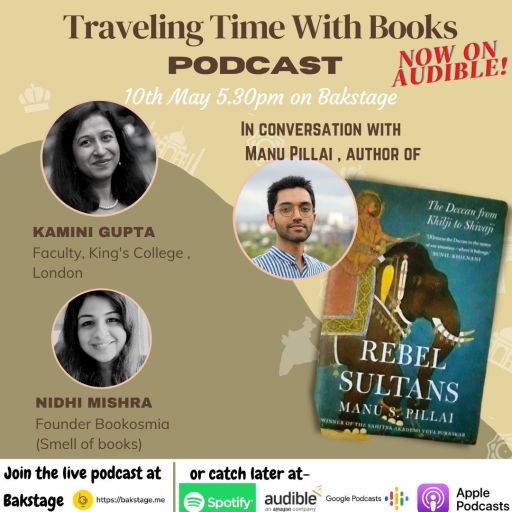

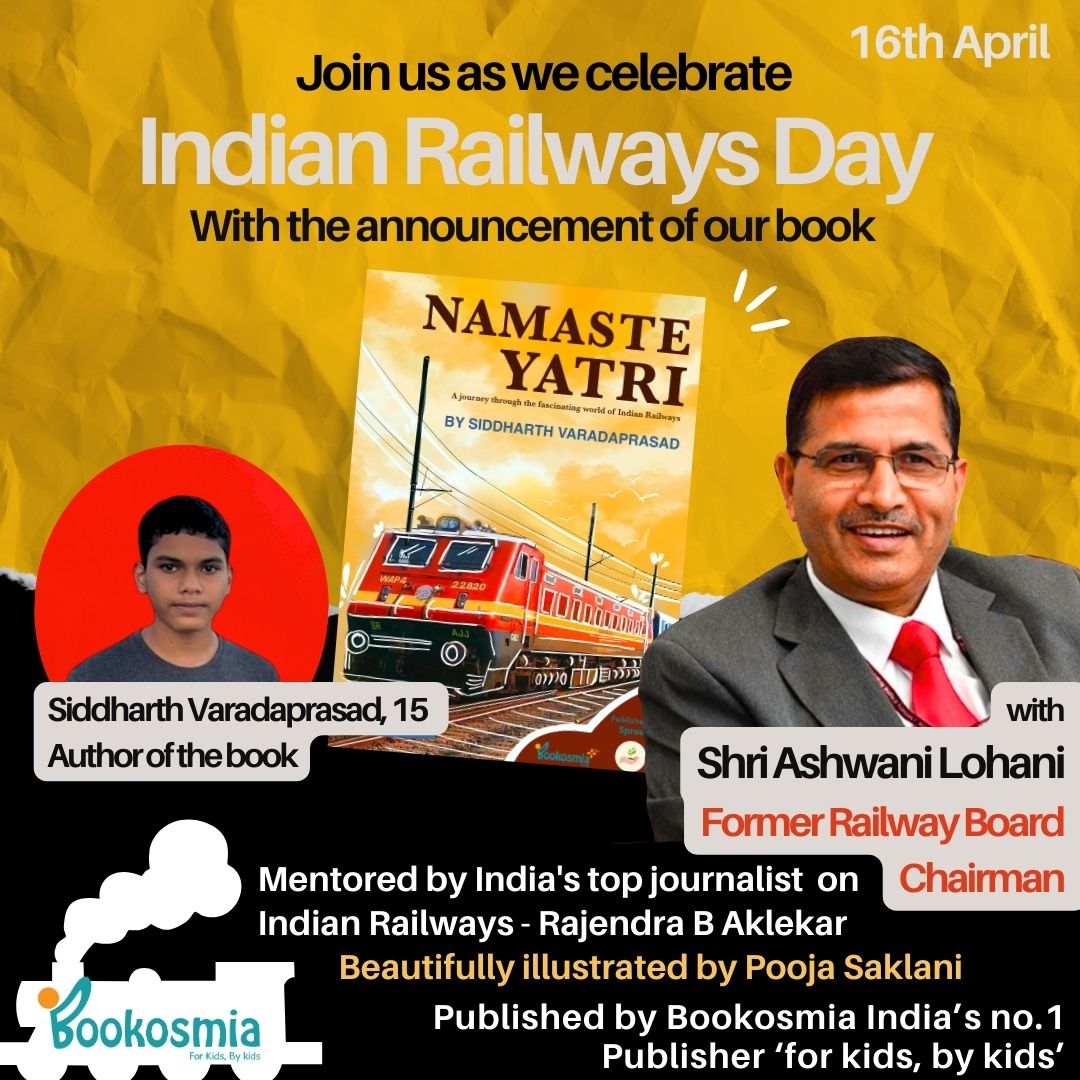

Nidhi is Founder & CEO of Bookosmia (smell of books) – India’s No.1 publisher of content ‘for kid, by kids’ from 140+ locations worldwide. An ex-banker who pivoted from a 10 year banking career to disrupt a traditional publishing industry, Nidhi attributes her love for literature and culture to growing up in Lucknow , her feminist flair and an Honours in Mathematics to Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University and an MBA and her husband to IIM Lucknow. After a decade-long career in the financial sector, finally quitting as VP, HSBC as she suffers from a (misplaced) sense of satisfaction and a drive to do something meaningful with her time. She has been on the editorial board of the international journal Borderless, is a neurodiversity ally and mental health advocate for adolescents. Outside of Bookosmia, Nidhi spends much of her time overindulging her two beautiful daughters, organizing dastangoi/mehfils and co-hosting a podcast with authors,called Traveling Time with Books on Audible, Spotify etc.You can write to her at nidhi@bookosmia.com