Sources tell the story, and historians spread it to the world I Blog By Rishav,13,Kolkata

Rishav from Kolkata writes a blog on how History is reconstructed using written, physical, visual, and oral evidence, classified as primary, secondary, or tertiary sources. While written records like the Epic of Gilgamesh and physical remains such as Mohenjo-Daro provide concrete insights, oral and visual sources need verification. By piecing together these fragments, historians craft a reliable narrative of humanity’s past.

Sources tell the story, and historians spread it to the world

History is an evidence-supported reconstruction of the past. Notice the use of the word evidence-supported. The question ‘Where does the evidence come from?’ arises. The answer is that archaeologists excavate or dig sites where they think historical evidence may be buried; that is what most people believe. They are wrong. This evidence is not only from buried objects, cities, or anything buried deep under the ground. There are many other types of historical evidence: written, oral, visual, and physical.

The reconstruction of the past is divided into two parts- ‘prehistory’ and ‘history’. Prehistory is the time before writing was invented whilst history is the time period after the creation of writing..

These evidences are separated into three types which are primary sources, secondary sources and tertiary sources. Primary sources are the ones created in the time or time periods of concern. They are the hardest to find but they are also the most trustworthy. Primary evidences provide direct description of the situation. These are mostly created by the witnesses who experienced the event or events first hand. Secondary sources are created after the time period or periods of concern, thus the name. They are mostly secondary sources that are created by scholars and they are usually reliable. Tertiary sources are those that compile or summarize other sources. These are mostly analytical or only a complication.

Let us explore ‘Written evidences’ first. Diverse nature of the written sources allows historians to look into the past from different aspects. Since prehistory is a time before writing, sadly, there is no written evidence from that time. After prehistory, when the Sumerians devised the first known script in circa 3200-3100 BCE, the ‘Fertile Crescent’ bloomed with writing. Pieces of literature such as the ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’ written in about 2150-1400 BCE came into existence. Letters such as the ‘Amarna Letter’, which provide insight into the diplomatic relations between Egyptians and other empires or nations, are a part of written evidences. Biographies such as ‘Harshacharita’ by Bana Bhatta narrating the life of Harsha, a 7th century CE Indian emperor, also play a part in knowing the life of the person.

Autobiographies help doing the same thing but also help in understanding the socio-political situation of a time period from the perspective of the person. Travelogues such as ‘Indica’ written by Megasthenes give us a description of India, though Indica is not fully factual. These, along with court or royal orders, make up most of the written evidences. Written sources are the only type of evidence that can be all the types of sources depending on the time of creation. Such as, ‘Ten Days That Shook the World’ by John Reed is a primary source as the author was a witness of the situation. Whilst, the website ‘World History Encyclopaedia’ is a tertiary source, as it compiles and analyses other sources.

As we go through the history texts, we see the dominance of written sources along with physical evidences often. Physical evidences are things which were made in a certain time period of the past and help reconstructing it. Physical evidences can be of many shapes and sizes. ‘Mohenjo Daro’, a city of the Harappan or better known as Indus Valley civilization; is a huge city. While pieces of ancient pottery found during the excavations at ‘Jericho’, the first town, are as small as a baby’s hand. Physical evidences are a huge part of constructing the tale of the past. They are an extremely important type of historical evidence because most of the time they are well preserved and any renovation done after the time of making or building can be identified by experts. They give us a credible insight of the technological advancements of the time. When examining objects of daily use we can reconstruct the daily life of people of that time. Tombs and burials give information about how people were buried and, depending on the materials used, how wealthy that person or his family was. Which in turn give us a peek into the socioeconomic situation of that time. Physical sources are always primary sources of history.

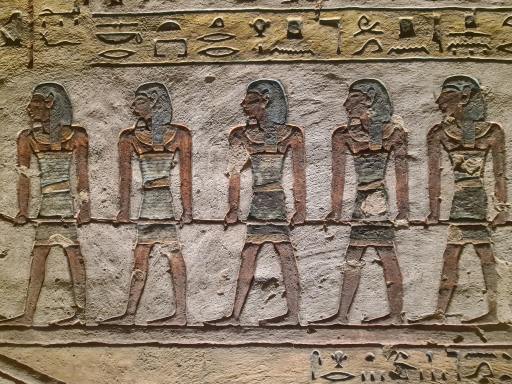

While going through the writings of the eminent historians and archaeologists, we see that all the primary sources are not equally powerful for them to recreate the past stories. For example, ‘Visual evidences’, although primary source, cannot match the strength of ‘Physical and Written evidences’. Visual evidences as the name suggests are visuals such as paintings, drawings and photographs. This type of evidence is found in both time periods. Cave painting were very frequently drawn as hunter gatherers used to believe this would bring them good luck. Paintings such as the one on the walls of Egyptian tombs of kings which accompany hieroglyphic writings are also example of visual evidence. The special thing about visual sources is that there is no one interpretation of it. Different people with different styles of thinking can make sense of it differently. This is why the most likely interpretation which is supported by physical, written or oral evidence. For example, a picture of a child. Imagine that in this picture the child’s eyes seemed red. Some may say his eyes were red from crying, some may say it was red from watching too much television. Oral evidence which is supplied by the people who were present at the time says it was red from watching too much television. This goes without saying that visual evidence, although regarded as primary source, can only be trustable when verified by written, physical or non-degraded oral evidence. Also, we can appreciate the changing character and quality of visual sources starting from pre-history cave paintings to artistic paintings of mediaeval times and photographs from early modern era.

History telling is never complete until we make full use of all possible sources evidence. Secondary sources like ‘Oral evidences’ is one such. Sometimes they can be useful to fill up the gaps in ‘Primary sources’. Oral evidences are a very non-trustable and volatile source of history. This source existed since the creation of spoken language. Imagine a person explains a conversation that took place between him and someone else to his friends. If we compare the description with the actual conversation the wording may not be same or some phrases or lines maybe missing from the description. Now imagine that description of the conversation is passed down from generation to generation. The original description may completely defer from the one remembered ten generations later. This is why sources are not trustworthy and have to be fact-checked by written, visual or physical evidences. Some oral sources are forgotten. Some have been concealed in folk songs and stories. Thus, oral sources are mostly secondary sources of history.

When all these types of evidences are put together they reconstruct a tale of how we came to be, the story of our ancestors and their lives and what happened thereafter. How we, the humans, established our intellectual dominance on the Earth. These evidences help us reconstruct a tale as old as time itself and call it ‘history’.

***

Bibliography:

- Vere Gordon Childe, WHAT HAPPENED IN HISTORY, English, 2nd ed. (1923; repr., New Delhi, India: Atlantic Publishers and Distributors (P) Ltd, 2024).

- Crawford, Michael, Emilio Gabba, Fergus Millar, and Anthony Snodgrass. Sources of Ancient History. English. 1st ed. 1983. Reprint, Cambridge, United States of America: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, H. C. Raychaudhuri, and Kalikinkar Datta, An Advanced History of India, English, 3rd ed. (1946; repr., New Delhi, India: MACMILLAN AND CO OF INDIA LTD, 1974).

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Ancient India, English, 11th ed. (1952; repr., New Delhi, India: Motilal Banarasidass Publishing House, 2022).

- Lipartito, Kenneth, ‘Historical Sources and Data’, in Marcelo Bucheli, and R. Daniel Wadhwani (eds), Organizations in Time: History, Theory, Methods (Oxford, 2013; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 Jan. 2014), https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199646890.003.0012, accessed 26 Aug. 2024.

- Bottéro, Jean. Gilgamesh, the king who did not wish to die. The UNESCO Courier: a window open on the world, 2009. Vol XLII; Issue 9, p. 18-21, illus. Available on https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000083935

Photo Credit – Copyright Free, Royalty Free images from Pexels

- Amarna Letter, archaeologists, Bana Bhatta, circa, evidence, Fertile Crescent, Harappan, Historians, Historical Sources, history, Indus Valley civilization, Jericho, Megasthenes, oral, Physical and Written evidences, physical., Pre history, Sharing History, socio-political, Sumerians, Ten Days That Shook the World, travelogues, trustworthy, visual, world, World History Encyclopaedia, written

6 Responses

I enjoyed the write-up, especially the style of writing. The author has the ability to keep the reader hooked on to the matter. Also, the content speaks volumes about the research that this school-going-yet-to-become-adolescent boy has done on this subject. Great going Rishav. Keep it up !

Thank You for your appreciation.

You are shaping history into a worth reading story. Great job. Waiting for your next writing.

Extraordinary informations ….. Excellent writing…… Keep it up 👍

Nice work. Keep going. Blessings.

Excellent, keep it up dear Rishav